Battle of Chancellorsville

The Battle of Chancellorsville is widely regarded as General Robert E. Lee’s greatest victory of the American Civil War. Fought in the Wilderness of Virginia from April 30 to May 6, 1863, Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia faced off against the reorganized and revitalized Army of the Potomac under Major General Joseph Hooker. “Fighting Joe” initially held the tactical advantage, but lost his nerve and yielded the initiative to Lee. Outnumbered by a Federal force that was nearly twice the size of his own, General Lee divided his army three times in a series of flank and frontal attacks that bewildered Hooker. The Union commander eventually pulled his forces back across the Rappahannock River, marking another humiliating defeat for the Army of the Potomac. Despite his brilliant victory, Lee lost one of his most trusted generals. During the battle, Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson was mortally wounded by friendly fire. Following the death of his highly capable subordinate, Lee professed, “I do not know how to replace him.” While nothing could make up for the loss of Jackson, Lee’s success at Chancellorsville earned him the strategic initiative. The Army of Northern Virginia would soon carry its momentum north to the small town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

In December 1862, General Lee delivered a crushing blow to the Army of the Potomac at the Battle of Fredericksburg. News of the defeat led President Abraham Lincoln to remark, “If there is a worse place than Hell, I am in it.” Fredericksburg was a disaster and morale in the Army of the Potomac sank to its lowest point during the winter of 1862-63. Major General Ambrose Burnside had presided over the catastrophe and Lincoln accepted his resignation in late January 1863, promoting Joseph Hooker to be the new commander of the Army of the Potomac. Hooker set about restoring confidence in the army, improving conditions for the soldiers including food, medical care, and leave. In late April 1863, the reenergized Army of the Potomac under “Fighting Joe” Hooker was ready to strike back against Robert E. Lee.

Major General Joseph Hooker. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Hooker was determined to use a campaign of maneuver to draw his Confederate adversary into the open for a decisive showdown. His confidence was high, reportedly saying, “May God have mercy on General Lee, for I will have none.” Hooker divided his massive army into three parts. 10,000 Union cavalry crossed the Rappahannock River far upstream and headed south to cut Lee’s supply lines. 70,000 northern infantry were sent upriver to cross at fords several miles beyond Lee’s left flank, while another 40,000 Federals feigned at Fredericksburg to hold Lee in place, giving the flanking force the opportunity to position itself into the Confederate left and rear. The Army of the Potomac brilliantly executed these complicated maneuvers. By the evening of April 30, Hooker’s 70,000 infantry were near a crossroads mansion called Chancellorsville, nine miles west of Fredericksburg in the middle of a dense second-growth forest called the Wilderness. The Army of Northern Virginia was outnumbered and gripped in an iron pincers. To General Lee’s aides, it was almost as if the new Union commander had copied one of their general’s old battle plans. In a congratulatory order to his men, Hooker declared that the “enemy must ingloriously fly,” or “give us battle on our ground, where certain destruction awaits him.”

Time and time again Robert E. Lee had bested the Army of the Potomac. Now, that same army under a new leader had him and the roughly 60,000 Confederates under his command in an extremely vulnerable position. Despite facing such unfavorable circumstances, General Lee decided not to retreat. Believing that the main threat came from the Union forces at Chancellorsville, Lee left some 10,000 infantry under Jubal Early to hold the Fredericksburg defenses, ordering the rest of his troops to march westward to the Wilderness. At mid-day on May 1, Confederate soldiers clashed with Hooker’s advance units a few miles east of Chancellorsville. In this area, the dense undergrowth gave way to open country, giving an edge to the Federals who could maximize their superior weight of numbers and artillery. Instead of pressing the attack, Hooker ordered his troops back to a defensive position around Chancellorsville. Here, the thick woods evened the odds for the outnumbered Rebels. Union corps commanders protested Hooker’s decision, but obeyed. General Lee sensed that he had a psychological edge over his opponent and decided to take the offensive despite being outnumbered nearly two to one.

Robert E. Lee. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

On the night of May 1, Lee and his masterful subordinate Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson sat on empty hardtack boxes, conversing by firelight about how to get at the enemy. Lee’s cavalry chief “Jeb” Stuart had the information that they needed. Stuart galloped up to the small campfire, bringing reports from his scouts that Hooker’s right flank was “in the air,” meaning that it rested on no natural or artificial obstacle, three miles west of Chancellorsville. Lee had the opportunity that he needed and Jackson was the man who would take advantage of it. To get his troops around to this flank unobserved, one of Jackson’s staff officers found a local resident to guide them along a track used to haul charcoal for an iron-smelting furnace. During the early hours of May 2, Jackson’s 30,000 infantry and artillery began their roundabout twelve-mile march to their attack position. Lee stayed in place with some 15,000 men to challenge Hooker’s main force. Under this strategy, General Lee defied a famous maxim of warfare, which warned against splitting one’s force in the face of a numerically superior enemy. Jackson’s flank march across the enemy’s front left him isolated from the rest of the army and left his strung-out column vulnerable to attack. Lee’s holding force would also be in great danger if Hooker discovered its weakness. The plan certainly had its risks, but believing that he held a psychological edge over the opposing commander, Lee counted on Hooker doing nothing while Jackson completed his march. To Lee’s benefit, Hooker fulfilled those expectations.

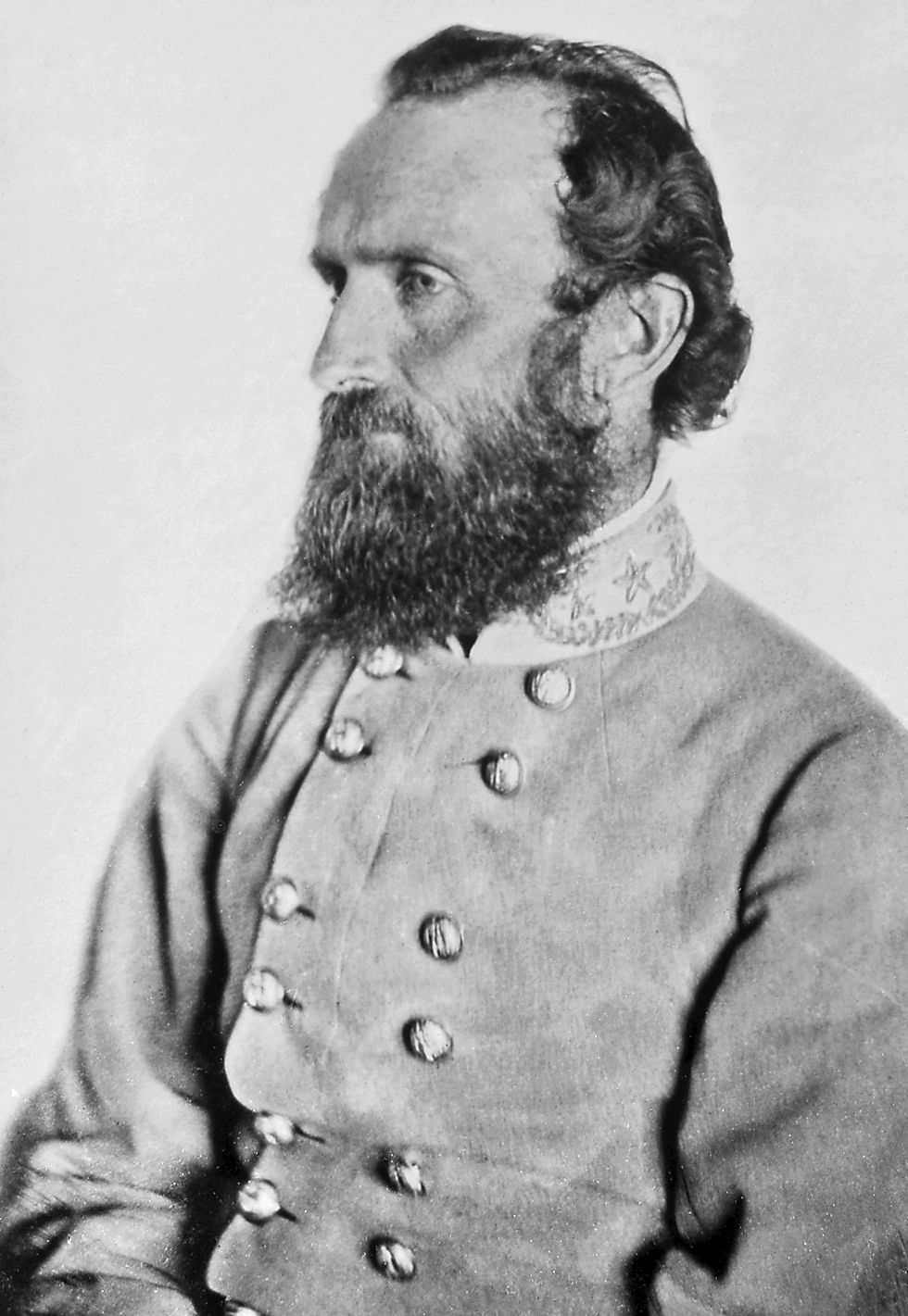

Two hours before dusk on May 2, Jackson hit the Union right flank with pile-driving force, shattering it to pieces and driving a whole Federal corps in a wild rout. Hooker’s army had been knocked completely loose from its prepared position. By dusk, Jackson had rolled up the Union right for two miles before Hooker and one of his corps commanders were able to establish a new line, bringing the Confederate advance to a halt. For several hours that night, sporadic and disorganized fighting took place, with some units mistakenly firing on their own men. One of the casualties in the moon-shadowed woods was “Stonewall” Jackson. While reconnoitering with several officers for a renewed attack, Jackson’s party was fired on by nervous Rebels who mistook them for Union cavalry. The man who had executed one of the most daring maneuvers of the entire war fell with two bullets in his left arm, which had to be amputated. “He has lost his left arm; but I have lost my right arm,” Lee famously said. Pneumonia set in and on May 10, the irreplaceable Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson died.

Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Following the flank attack on May 2, two or three days of confused and desperate fighting ensued around Chancellorsville and back at Fredericksburg. In the end, Hooker decided to retreat, pulling all of his troops north of the Rappahannock River. He never recovered after losing the initiative to Lee. Iconic Civil War historian James McPherson put it best, writing, “Like a rabbit mesmerized by the gray fox, Hooker was frozen into immobility and did not use half his power at any time in the battle.” Although Lee expressed regret that the Federals escaped destruction again, he had still achieved an astounding victory.

The price of victory for the Army of Northern Virginia came at a great cost. The Confederates suffered some 13,000 casualties, 22 percent of their force. Most severe of all was the loss of Jackson, who had done so much to make the victory possible. His absence would be felt by the Confederacy for the remainder of the war. While Lee had certainly lost one of his best men, the strategic initiative was now in his hands. As he moved north, Lee would enter his next major battle against the Army of the Potomac believing that his soldiers would “go anywhere and do anything if properly led.”

Robert E. Lee at Chancellorsville. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Union losses at the Battle of Chancellorsville were around 17,000 casualties, 15 percent of their force. The next time that the Army of the Potomac faced Robert E. Lee, it would be on northern soil. Before the decisive showdown at Gettysburg, Joseph Hooker was relieved from command and was replaced by George Gordon Meade. Under Meade’s leadership, the Army of the Potomac would have its finest hour on the fields of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

Sources

Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era by James M. McPherson.

Civil War Trust: 10 Facts: Chancellorsville.

Civil War Trust: Chancellorsville.

Civil War Trust: Joseph Hooker.

Hallowed Ground: A Walk at Gettysburg by James M. McPherson.

History.com: Battle of Chancellorsville.

National Park Service: Battle of Chancellorsville History: The Flank Attack.

The Civil War by Bruce Catton.

The Man Who Would Not Be Washington: Robert E. Lee’s Civil War and His Decision That Changed American History by Jonathan Horn.